February 15, 2021

February 15, 2021

Everything is different, and yet the same, business operations have changed beyond recognition with most employees working from home in a transition that happened almost overnight. Stretched team-mates and employees have been challenged to rapidly deploy robust remote working facilities to maintain productivity while most HR professionals are re-writing the ‘pandemic playbook’ as they go along. Most would agree that the new normal that begins to take shape in 2021 won’t be the old one. By forcing us from our routines, the pandemic has prompted us to re-examine the ways we live and work, and how we mix life and work together. We have the opportunity, and nearly a year’s worth of learnings, to fix inefficient workplace processes and protocols and start forging a better workplace now.

With this in mind, the following are the trends we expect to play a major role in the future of work, which is shaping up to be a bright spot for employees and companies alike.

Remote work

At the cusp of April 2020, one of the primary questions that many organizations were involuntarily faced with was ‘how do we keep the wheels turning?’. Here we were, at the brink of a novel global pandemic, uncertain of what havoc it would or would not wreak, add to it the question of distance-motivation, distance-employee-engagement, and of course productivity. Would it all work, from our couches?

A year since work from home has become the only option. There were and still are several issues with this working style, such as the strains of cohabiting with our families, partners, and/or even pets; ergonomic furniture; the innumerable distractions of door-bells and deliveries, and so on.

In several parts of the world including the UAE and KSA, WFH has now become the new normal. with several companies abandoning the initial anxiety of non-performance, seeing spikes in productivity and sales, so much so that many companies have now decided to not renew their office leases.

Businesses of course have had to restructure protocols and systems to accommodate this innovative and sustainable style of work, which has resulted in both increased productivity and hence sales and in most cases, happier employees.

Human Resources, Social Media and reinventing the employee experience

If you think back to the pre-COVID world, you can see the employee selection process as a rather simple one. A candidate submits his or her CV, if shortlisted goes through an interview process in the offices, then a screening process, and so on. Eventually, the new addition to the company is welcomed by the manager and integrated into the team.

Now, think of the same procedure in the post-COVID world.

HR would have to design a process with everything being conducted seamlessly over the internet.

This would include the initial submission of the resumes, short-listing, rounds of zoom interviews, psychometric tests, and more, except, without any real one-on-one with the candidate.

This is where the mettle of HR comes into play.

In addition to ensuring that the right selection of candidates has been made, HR has the additional onus of devising clever ways to incorporate engagement, collaboration, teamwork, communication, and wellbeing for purposes of optimization of the company. If you make the new recruit feel connected, even if they are not physically greeted, you will have loyal and motivated employees on your side, and HR is quite aware of this.

If nothing else, 2021 will certainly see Human Resources professionals thinking out of the box and innovating creative ways forward, for new recruits and old. And, we are already seeing glimpses of creativity as HR professionals leverage social media platforms, to find the right fit for the right company.

Needless to say that this isn’t entirely ‘new’ but the fact that 85% of companies now say they use social media recruiting and candidate nurturing successfully and understand that their competitors will be on these sites wooing potential talent, is a leap from the previous decade in the recruitment industry.

Moving on to 2021, there’s no doubt that companies have to adjust their normal methods when it comes to sourcing and hiring the best talent they can, to stay viable in an increasingly competitive and volatile market. On the other hand, HR strategies are now more flexible than ever before, and there are multiple channels open for enterprising companies willing to do the leg work.

Though times have changed, the fundamental goal of hiring is still the same: to get as close a possible match between the company’s needs and the candidate’s competencies. The only difference today is that businesses are expected to carry out a more sophisticated, targeted, and intelligent survey of the prospective workforce than perhaps ever before and that will only get stronger 2021 onward, except as previously mentioned, mostly virtually.

Regulations galore

No one particularly likes regulation, until things go awry.

The European Union is likely to continue to evolve its stance on GDPR which inevitably affects the big tech companies that have been such darlings of the markets for the last few years and which are now subject to greater and greater levels of distrust and anti-trust lawsuits.

One of the most jarring confluences of regulators, tech companies, and users in recent months has been the way US President Donald Trump has very effectively used platforms like Twitter to get his particular message out to market.

In response to the recent violence which took place at the US Capitol, a number of platforms, including Twitter, banned the president from their platforms, inevitably sailing very close to being the arbiters of free speech and justice; behaviour which is arguably well outside their purview.

The crisis sparks a wave of innovation and launches a generation of entrepreneurs

Plato was right: necessity is indeed the mother of invention. During the COVID-19 crisis, one area that has seen tremendous growth is digitization, meaning everything from online customer service to remote working to supply-chain reinvention to the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning to improve operations. Healthcare, too, has changed substantially, with telehealth and biopharma coming into their own.

Disruption creates space for entrepreneurs—and that’s what is happening in the United States, in particular, but also in other major economies. We admit that we didn’t see this coming. After all, during the 2008–09 financial crisis, small-business formation declined, and it rose only slightly during the recessions of 2001 and 1990–91. This time, though, there is a veritable flood of new small businesses. In the third quarter of 2020 alone, there were more than 1.5 million new-business applications in the United States—almost double the figure for the same period in 2019.

Yes, many of those businesses are single-person establishments that could well stay that way—think of the restaurant chef turned caterer or the recent college graduate with a cool new app. So it’s intriguing that the volume of “high-propensity-business applications” (those that are likeliest to turn into businesses with payrolls) has also risen strongly—more than 50% compared with 2019. Venture-capital activity dipped only slightly in the first half of 2020.

The European Union has not seen anything like this response, perhaps because its recovery strategy tended to emphasize protecting jobs (not income, as in the United States). That said, France saw 84,000 new business formations in October, the highest ever recorded, 7% and 20% more than in the same month in 2019. Germany has also seen an increase in new businesses compared with 2019; ditto for Japan. Britain is somewhere in between. A survey published in November 2020 of 1,500 self-employed people found that 20% say they are likely to leave self-employment when they can. 8 At the same time, however, the number of new businesses registered in the United Kingdom in the third quarter of 2020 rose 30% compared with 2019, showing the largest increase seen since 2012.

On the whole, the COVID-19 crisis has been devastating small businesses. In the United States, for example, there were 25.3% fewer of them open in December 2020 than at the beginning of the year (the bottom was in mid-April when the figure was almost half). 10 US small-business revenue fell more than 30% between January and December 2020. 11 But we’ll take good news where we can get it, and the positive trend in entrepreneurship could bode well for job growth and economic activity once the recovery takes hold.

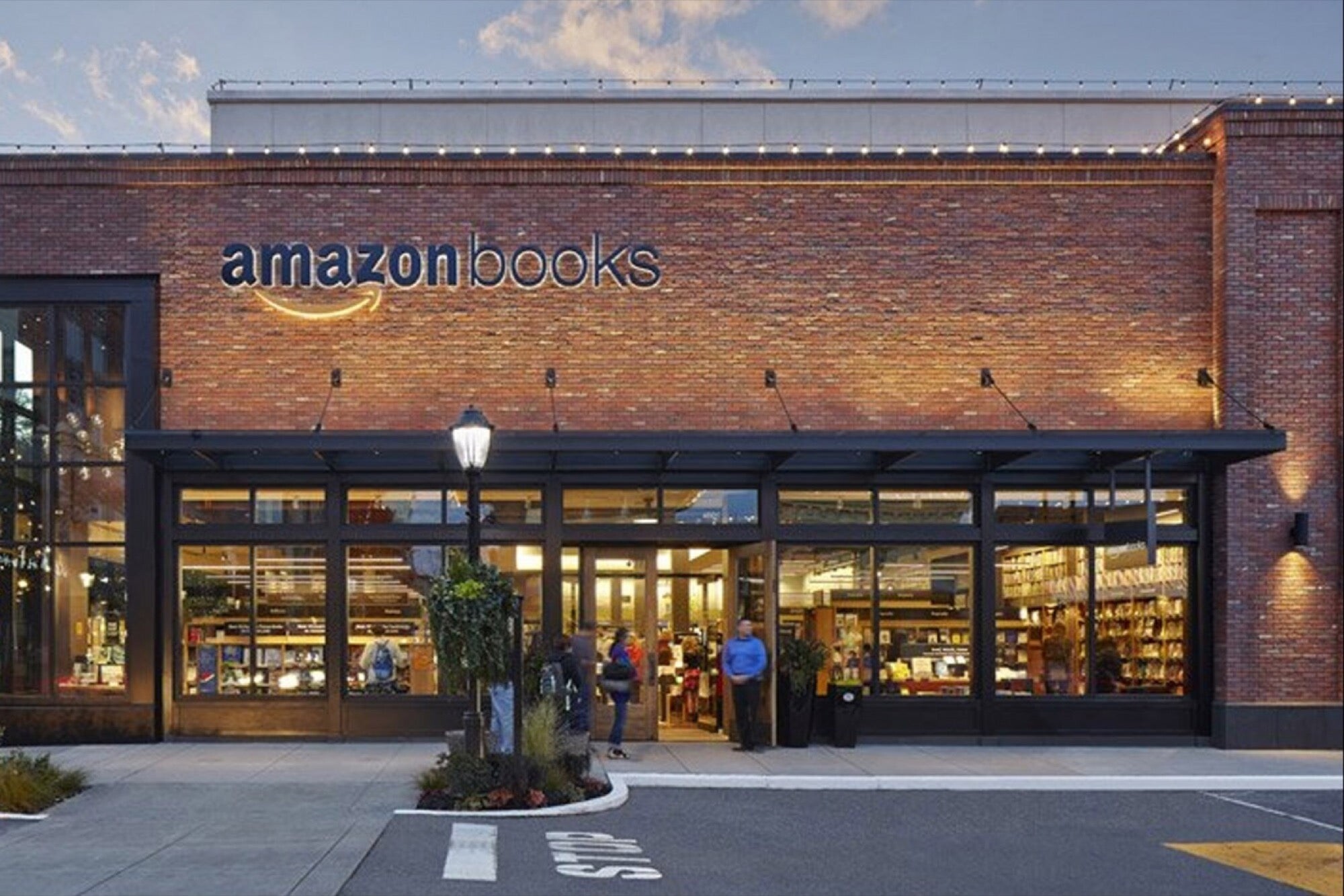

Brick-and-mortar disruptions are permanent

Stating the United States as an example, nearly half of economists surveyed by the National Association for Business Economics (NABE) state that the U.S. GDP won’t recover until 2022 or later.

But there’s a silver lining for organizations that are prepared for e-commerce. Drastic changes in people’s behaviours are creating immense opportunities for online retailers. Secondly, e-commerce firms can learn from bargain stores because consumers are looking to stretch their purchasing power owing to the shrunken personal and collective household spending power. If you operate an online store, don’t ignore merchandise and items that are practical and which represent value purchases for struggling consumers.

Additionally, the COVID-19 crisis provoked divergent, even dramatic, reactions, with some industries taking off and others suffering; the effect was to shake up historic norms.

When the economy settles into its next normal, such sectoral differences can be expected to narrow, with industries returning to somewhere around their previous relative positions. What is less obvious is how the dynamics within sectors are likely to change. In the previous 2008 downturn, the strong came out stronger, and the weak got weaker, went under, or were bought.

The defining difference was resilience—the ability not only to absorb shocks but to use them to build a competitive advantage. Over the course of a decade, companies can expect losses of 42% of a year’s profits from disruptions.

Top performers won’t sit on their strengths; instead, as in previous downturns, they will seek out ways to build them. That’s why we expect to see substantial portfolio adjustment as companies with healthy balance sheets seek opportunities in the context of discounted assets and lower valuations. In fact, that may already be happening: deal-making began to pick up midyear 2020.

Much more important is private equity (PE). Globally, PE firms are sitting on almost $1.5 trillion of “dry powder”—unallocated capital that’s ready to be invested.

The COVID-19 crisis has hurt in some ways, with global deal value down 12% compared with the first three-quarters of 2019 and deal counts down 30%.

On the other hand, global fundraising has stayed strong—$348.5 billion through September 2020, on par with the previous five years—and deal-making in Asia has more than doubled. The PE industry has a reputation for zigging when others are zagging, making deals in difficult times. And it has history on its side: returns on PE investments made during global downturns tend to be higher than in the good times. Put it all together, and we don’t think the PE industry is going to keep its powder dry for much longer; there are simply going to be too many new investment opportunities.

The return of confidence unleashes a consumer rebound

There are lines outside stores, but they are often due to physical-distancing requirements. The theatre’s are dark. Couture is in closets rather than on display. If the Musée du Louvre were open, the lack of tourists might even create the opportunity for an unobstructed view of the Mona Lisa. In these and other ways, consumers have evidently pulled back.

As consumer confidence returns, so will spending, with “revenge shopping” sweeping through sectors as pent-up demand is unleashed. That has been the experience of all previous economic downturns. One difference, however, is that services have been particularly hard hit this time. The bounce-back will therefore likely emphasize those businesses, particularly the ones that have a communal element, such as restaurants and entertainment venues.

That isn’t to say that consumers will act uniformly. One recent consumer survey, published in October 2020, found that countries with older demographics, such as France, Italy, and Japan, are less optimistic than those with younger populations, such as the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, India, and Indonesia. China was an exception—it has an older population but is conspicuously optimistic.

But China’s profile proves a larger point. The first country to be hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was also the first to emerge from it. China’s consumers are relieved—and spending accordingly. On Singles Day, November 11, the country’s two largest online retailers racked up record sales. That wasn’t just a holiday phenomenon. While manufacturing in China came back first, by September, so had consumer spending. Except for international air travel, Chinese consumers have begun to act and spend largely as they did in pre-crisis times. Australia also offers hope. With the pandemic largely contained in that country, household spending fuelled a faster-than-expected 3.3% growth rate in the third quarter of 2020, and spending on goods and services rose 7.9%

How fast and deep confidence will recover is an open question. In late September, for example, the US consumers surveyed were more optimistic than before but still cautious, reporting that they planned to buy holiday gifts for fewer people and keep an eye on discretionary spending. 2 Only around a third had resumed out-of-home activities, compared with 81% of consumers in China, 49% in France—and just 18% in Mexico. New lockdowns and, critically, the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines have and will affect those numbers. The point is that spending will only recover as fast as the rate at which people feel confident about becoming mobile again—and those attitudes differ markedly by country.

Digitally enabled productivity gains to accelerate the Fourth Industrial Revolution

There’s no going back. The great acceleration in the use of technology, digitization, and new forms of working is going to be sustained. Many executives reported that they moved 20 to 25 times faster than they thought possible on things like building supply-chain redundancies, improving data security, and increasing the use of advanced technologies in operations. 12

How all that feeds into long-term productivity will not be known until the data for several more quarters are evaluated. But it’s worth noting that US productivity in the third quarter of 2020 rose 4.6%, following a 10.6% increase in the second quarter, which is the largest six-month improvement since 1965. 13 Productivity is only one number, albeit an important one; the startling figure for the United States in the second quarter was based in large part on the biggest declines in output and hours seen since 1947. That isn’t an enviable precedent.

More positively, in the past, it has taken a decade or longer for game-changing technologies to evolve from cool new things to productivity drivers. The COVID-19 crisis has sped up that transition in areas such as AI and digitization by several years, and even faster in Asia. A survey published in October 2020 found that companies are three times likelier than they were before the crisis to conduct at least 80% of their customer interactions digitally. 14

The COVID-19 crisis has created an imperative for companies to reconfigure their operations—and an opportunity to transform them. To the extent that they do so, greater productivity will follow.

That evolution has not always been a seamless or elegant process: businesses had to scramble to install or adopt new technologies under intense pressure. The result has been that some systems are clunky. The near-term challenge, then, is to move from reacting to the crisis to building and institutionalizing what has been done well so far. For consumer industries, and particularly for retail, that could mean improving digital and omnichannel business models. For healthcare, it’s about establishing virtual options as a norm. For insurance, it’s about personalizing the customer experience. And for semiconductors, it’s about identifying and investing in next-generation products. For everyone, there will be new opportunities in M&A and an urgent need to invest in capability building.

The race for a vaccine and its logistics

This year will be more about the vaccines deployed against the disease than the disease itself. South Africa plans to vaccinate its healthcare workers by the end of February, a noble and well-placed goal, and 20 million South Africans by the end of the year.

Arguably, this latter goal is ambitious from a logistical point of view. There are also likely to be difficulties acquiring and even financing suitable quantities of the vaccine.

For context, the Philippines has a population of 100 million people. It plans to vaccinate 100% of its population – but only by 2023.

The cause for optimism is that at least five major vaccines are available to the world: the three major ‘Western’ vaccines and one each in Russia and China, together with a number of others in various stages of global development.

The key trend for 2021 then is for extended periods of variations on lockdown to buy time with which to achieve herd immunity. The lighter the lockdown and the sooner immunity is achieved the less economic damage. On the other hand, the longer this takes the more likely the economic damage is to be of the kind that cannot be recovered from.

When it comes to the logistical transportation technology involved in early vaccine candidates require ultra-low temperatures, as much as -70 degrees Celsius©, or -94 degrees Fahrenheit. This is influenced by a lack of data storage specifications and shelf life for these new types of Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines. The containers to store and transport them are not widely available and not required for common vaccines. Constant temperature control is needed E2E from the manufacturing site to the inoculation sites. According to known criteria, people will require two vaccines from the same manufacturer within a specific time frame.

That equates to more than 662 million doses in the United States and approximately 1.5 billion across the European population.

Drug companies like Pfizer and logistics giants DHL and UPS are working together on expected supply chain gaps, including logistics and freezer farms.

Questions remain about the providers of these ultra-cold freezers. One such company is Cryoport, with its C3 Ultra Cold solution dry ice shipper that can keep commodities at temperatures of -60 to -90° C. These suppliers are not particularly large companies. And not many offer transportable options (versus upright freezers from ThermoFisher Scientific). In question is their ability to scale or the capabilities of their supply chain down to the raw materials.

Much of the focus, to date, has been on fulfilment centre’s and modal capacity for air and road. Another concern is the need to seamlessly track temperatures and provide alerts for any out-of-spec loads. This involves integrated software, sufficient compute and sensor capabilities throughout, and the cooperation of both public and private entities across multiple modes and likely competitors. The search for critical Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and ventilators this spring unveiled dependencies on China sourcing, challenges scaling at a global level, and a lack of awareness of suppliers’ suppliers. The scale of technology, strategy, and operations excellence needed will require transparency, flexibility, and scale never seen, and will take herculean efforts beyond the actual vaccine development and approval.

The biopharma revolution takes hold

The announcement of several promising COVID-19 vaccines has been a much-needed shot of good news. There will be challenges to rolling out these vaccines on the scale needed, but that does not lessen the accomplishment.

Unlike previous vaccines, many of which use an inactivated or attenuated form of a virus to create resistance to it, the vaccines created by Moderna and the BioNTech–Pfizer partnership use mRNA. This platform has been under development for years, but these are the first vaccines that have secured regulatory approval. The “m” is for “messenger” because the molecules carry genetic instructions to the cells to create a protein that prompts an immune response. The body breaks down mRNA and its lipid carrier within a matter of hours. (WHO lists 60 candidate COVID-19 vaccines that have advanced to clinical trials; many don’t use mRNA.)

Just as businesses have sped up their operations in response to the COVID-19 crisis, the pandemic could be the launching point for a massive acceleration in the pace of medical innovation, with biology meeting technology in new ways. Not only was the COVID-19 genome sequenced in a matter of weeks, rather than months, but the vaccine rolled out in less than a year—an astonishing accomplishment given that normal vaccine development has often taken a decade. The urgency has created momentum, but the larger story is how a wide and diverse range of capabilities—among them, bioengineering, genetic sequencing, computing, data analytics, automation, machine learning, and AI—have come together.

Regulators have also reacted with speed and creativity, establishing clear guidelines and encouraging thoughtful collaboration. Without relaxing safety and efficacy requirements, they have shown just how quickly they can collect and evaluate data. If those lessons are applied to other diseases, they could play a significant role in setting the foundation for the faster development of treatments.

The development of COVID-19 vaccines is just the most compelling example of the potential of what MGI calls the “Bio Revolution”—biomolecules, biosystems, bio machines, and biocomputing. In a report published in May 2020, MGI estimated that “45% of the global disease burden could be addressed with capabilities that are scientifically conceivable today.”

For example, gene-editing technologies could curb malaria, which kills more than 250,000 people a year. Cellular therapies could repair or even replace damaged cells and tissues. New kinds of vaccines could be applied to noncommunicable diseases, including cancer and heart disease.

The potential of the Bio Revolution goes well beyond health; as much as 60% of the physical inputs to the global economy, according to MGI, could theoretically be produced biologically. Examples include agriculture (genetic modification to create heat- or drought-resistant crops or to address conditions such as vitamin-A deficiency), energy (genetically engineered microbes to create biofuels), and materials (artificial spider silk and self-repairing fabrics). Those and other applications feasible through current technology could create trillions of dollars in economic impact over the next decade.